Our first baseball off-day and we spent it traveling throughout the area. From Hiroshima we headed out to Iwakuni, Miyajima, and then back to Hiroshima to see the Peace Memorial.

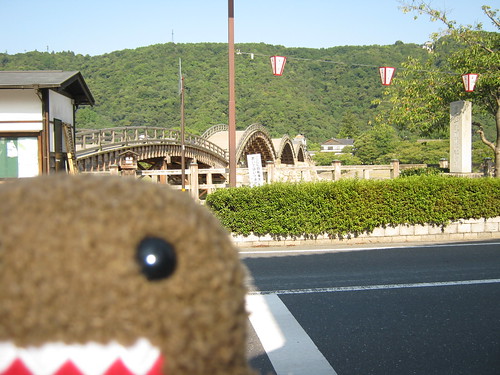

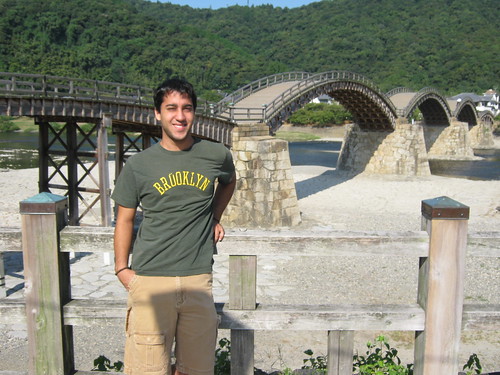

The morning started off with the usual optional day tour to see the sights in the area. Dave and I were eager to head to Iwakuni and see the famous samurai bridge Kintai-kyo. Historical accounts state that the bridge was only usable by the samurai caste back in the day and the whole thing was constructed completely without nails.

Like most monuments or historical buildings in Japan, the original bridge was destroyed by a typhoon, but was faithfully recreated in precisely the same way (although I think they used nails in certain key places to prevent future typhoon damage).

Across the bridge, up on the hillside, sits the also-famous Iwakuni Castle, so we paid our combined admission fee to cross the bridge, take the gondola up the hill, and see the castle.

The bridge itself was pretty cool and it allowed for some great views of the Nishiki River below us. Across the bridge is a town sort of devoted to tourism and the maintenance of the grounds. There are a bunch of shops, some cool photo opportunities, and a shrine near the gondola to pray and make offerings at.

Of course, you can’t get up a giant slope (easily) without a gondola, so we queued up and learned that the tiny cars we’d be taking to the summit were supposed to fit 30 people. That would be 30 Japanese people, mind you, so beyond the usual size increase that you can expect from Americans, our tour did include some of the larger, stereotypical type. It made for a crammed space that would be hell for the claustrophobic and was also uncomfortably hot thanks to the sun shining through the windows. Insult was added to injury as one of the Japanese operators made a gesture by puffing out his cheeks and holding his arms out to the effect that we were fat Americans and laughed at us. As a non-fat American, I wasn’t too bugged by this, but it was a remarkably rude action considering that the Japanese make an effort to be polite 99% of the time.

One remarkable view later, we were at the top of the mountain/hill thing looking out over the beauty of the Iwakuni landscape. A short walk up the tourist path took us to Iwakuni Castle.

I think the thing I love most about going to culturally distinct (read: non-Western) parts of the world is seeing the way that they developed along parallel, but wildly different paths. One of the most obvious examples of this is the way that the East and West designed castles. We’ve all seen plenty of Western castles. They’ve got ramparts and they’re surrounded by walls, etc. Eastern castles all have verticality and tend to look a bit like pagodas. For all their differences, one thing they both (can) have in common would be the inclusion of moats.

Iwakuni Castle was nothing too special, its floors were filled with museum pieces that you might expect, samurai armour, old pictures of the areas, a model of the bridge, swords, firearms, and decorative pieces, while its top floor housed an observatory deck. We headed back down the gondola and caught a train to Hatsukaichi to see the famous Miyajima (shrine island).

Why is the island so famous? It’s got an ever popular and often photographed Shinto-style torii (gate). Chances are, you’ve seen a picture of this at some point in your life. To get to the island, we boarded a ferry and Susan told Dave and I about the robust deer population. While it’s not as intense as the deer population on Nara, Miyajima is full of seriously domesticated/adjusted deer who don’t even react to human proximity. No lie, I accidentally stepped on one while taking a picture and the little guy didn’t even react to me nudging it with my feet.

My favorite moment on the island had to be when we came upon a group of Japanese guys taking a picture holding up Bullwinkle-style antlers to his head while next to a buck. When we asked them to take a photo, he instead opted to throw up a different set of horns, which was also pretty awesome, so I forgive him.

We got some fantastic shots near the gate and started to head back to the ferry when we were lured into an oyster shop by an enterprising saleswoman. At great risk for missing the ferry and being separated from the tour group, we waited for her to cook the oysters and then made a mad dash, oysters in hand, to the ferry to the mainland.

The oysters were fantastic. So fantastic, they deserved their own paragraph.

With that, our morning was over and we had seen two great sights. There was still plenty of day to go, so we hopped aboard a train headed back to Hiroshima. Our destination would be just outside the A-Bomb Dome.

There is something powerful and deeply affecting about standing 150 meters away from where the first atomic bomb attack occurred. Plain and simple, I stood in complete awe as I took in the Genbaku Dome (AKA A-Bomb Dome, AKA Hiroshima Peace Memorial), saw its bare walls barely standing, its dome a stripped husk of steel, and then looked around at the Hiroshima that surrounded it, fully rebuilt, fully alive, and fully defiant of the atrocity that took place in that very spot 64 years ago. I say atrocity, not because I find the reasons behind the atomic bomb to be faulty, but because I find war atrocious. 70,000-80,000 people died as a result of that bomb. The Aloi Bridge, intended target, stood behind me, but the actual hypocenter was 240 meters from that, above the former Shima Surgical Clinic. I’m not going to get too much deeper into this, but if there’s one thing I took from standing outside that dome, it’s that atomic bombs should never be used again.

From the dome, Dave and I wandered around Hiroshima, noticing statues that bore evidence of the blast and were used to determine the hypocenter. Eventually we came across the Children’s Peace Monument, dedicated to the memory of Sadako Sasaki, a hibakusha (literally “explosion-affected people”) who did not develop leukemia until ten years after the bomb. Desperate to live, she began folding paper cranes with the idea that by folding 1000 paper cranes, she would be granted a wish, according to a Japanese saying. While she did fold over 1000 paper cranes, she still died at age 12 from radiation she was exposed to ten years prior.

The monument itself is nice and it’s surrounded by transparent rooms containing thousands of paper cranes sent in by children around the world.

From the monument, we wandered toward the Memorial Peace Park and the museum, stopping to take note of the Memorial Cenotaph, which contains the names of all hibakusha who have died and the Peace Flame, which is not an eternal flame, per se. Its fires will be extinguished only when there are no longer any nuclear bombs on the planet and we are “free from the threat of nuclear annihilation.”

Anyone who remembers the huge controversy a few years ago between Japan and China over Japanese textbooks omitting atrocities they committed in World War II knows that Japan, unlike Germany where it is illegal to deny the holocaust or display Nazi iconography, has sometimes tended to forget about their role in WWII. With that in mind, I entered the museum and found that, contrary to expectations, the museum was almost completely even-handed in its treatment of the subject. The message was clear: nuclear weapons are evil and should be eliminated, but there was almost no Japanese bias. In fact, the only Japanese “spin” was that World War II was called the Pacific War, the name it’s given within the country. I came out of the museum deeply affected by the accounts of the victims, some small children, who were incinerated, had the flesh burned off their bodies, or just suffered complications further in life as a result of a blast that couldn’t have lasted longer than half a minute. Stories of victims flinging their still burning bodies into the river for relief took shape within my mind and, despite my already pacifist leanings, I think I left there with a changed point of view about how completely unnecessary wars of aggression are and just how dire the consequences can be.

Our long day was finally over, so we went back to the hotel to relax and rest up for dinner that night. On the menu, yakiniku. Unfortunately, I left my camera at home by accident, so I don’t have any pictures of the fun.

For those unfamiliar with the term, yakiniku is a Korean style barbeque where grills are set in the table in front of the customers and raw meat is brought out (typically in an all-you-can-eat in a certain amount of time style) for the patrons to cook and eat. It’s fantastic and I have yet to find a good, authentic (to the degree that the Japanized version of a Korean style of cooking can be) Korean BBQ place in the States.

Thanks, in small part, to the insistence of Dave, Susan, and myself, we also convinced Bob and Mayumi that we absolutely had to go to a karaoke box that night to truly get a feel for Japan. Demand to sing was so high that we had to rent out two rooms for our party and we sang well into the night to the likes of Queen, Neil Diamond, Garbage, Gackt, Madonna, and The Beatles. It works something like this:

1. You enter the room with an agreed-upon rate per hour (or per person per hour in some cases).

2. Drinks are ordered via a telephone in the room.

3. There is a television in the room and a small computer in which participants can enter the numeric codes (found in the songbooks) of the song they’d like to sing

4. Song starts.

5. People sing.

6. Repeat steps 3-5 until you are hoarse, tired, or both.

It was a total blast and I’m glad that I’ve spent so much time destroying people’s eardrums in Rock Band that I was barely nervous at all about singing. Our room was full of energy and nearly everyone sang until midnight.

It was time to go back to the room and sleep, tomorrow we would return to baseball (and Tokyo!).

Leave a Reply