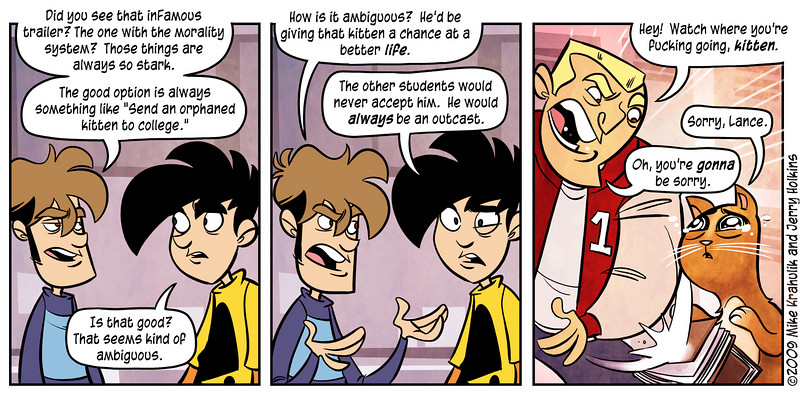

…like many mechanisms of this kind your choices tend to come down to being an omnibenevolent supercherub or the Goddamned devil.

-Jerry “Tycho” Holkins

WARNING: SPOILERS

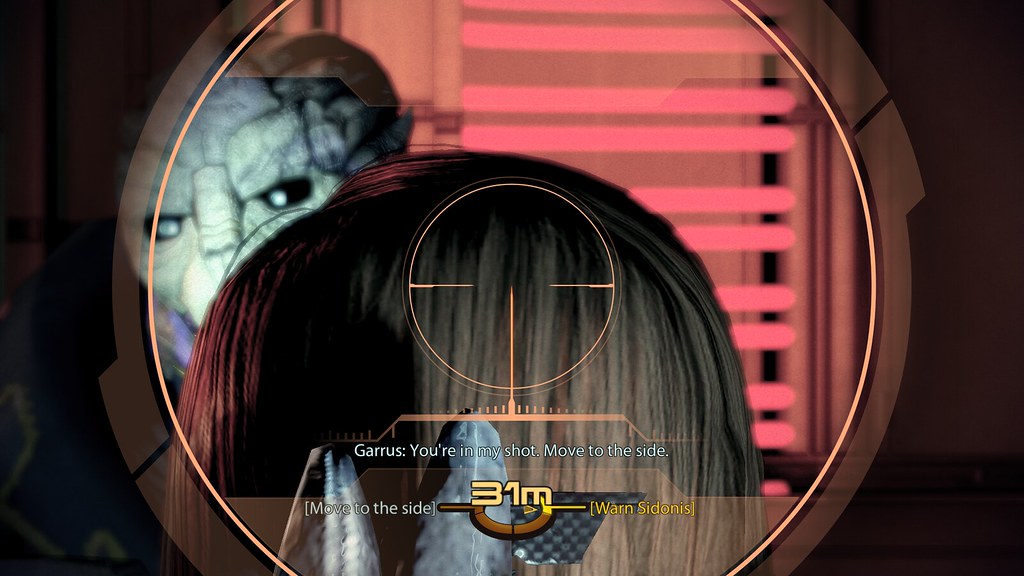

A member of your crew was double-crossed before he joined you. Eleven of his friends died as a result of that treachery and he wants revenge on the killer. Do you: A) Indulge his obsession and allow him to murder in cold blood when his target least expects it or, B) Convince him that his obsessive revenge will not bring him the closure he desires by obstructing his revenge attempt.

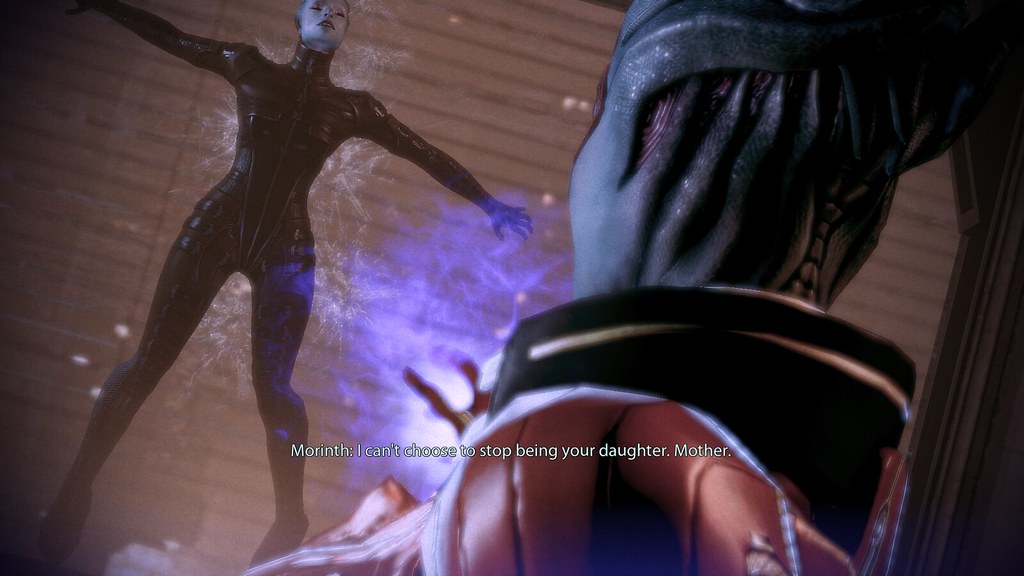

Later on a member of your crew who has been hunting a serial killer for hundreds of years asks you to help her bring said criminal to justice. The killer is a genetic aberration in her species who kills everyone she mates with (her species can mate with any species) and derives both power and an almost narcotic effect from her murders. There’s also the extra angle that this killer is the daughter of your party member, a woman who birthed three such monsters and had the other two locked away in isolation for the simple crime of their genes. Do you A) side with your crew and murder this killer to end her spree or B) side with the killer and kill your crewmate, ultimately gaining this serial killer as a party member and allowing her to escape free after your mission.

One of these two represents an actual moral choice worth thinking about while the other is noticeably less complex and, consequently, far less interesting. It may not be as obvious a choice as mass murder a crowd or buy them all ice cream, but it’s still pretty basic when you look at it. Will revenge really give Garrus closure? Does letting Sidonis live with his guilt represent a greater punishment? These are things we’ve confronted plenty of times before in these games. “Murder or mercy” is the bread and butter of the morality system, but it’s been seven years since Knights of the Old Republic and we need to up the ante here a little (Yes, I’m aware that morality systems have existed long before KoTOR. Giant Bomb lists 168 of them). In fact, Dragon Age: Origins, another Bioware game that came out in 2009, featured a system that puts this game’s choices to shame.

Perhaps it’s because DA:O was in development since 2004 (that’s five years to its release in 2009) while Mass Effect 2 has only a scant three years under its belt, but almost everything about the “morality system” in Dragon Age far exceeds what’s available to the player in ME2. To start with, Dragon Age dispenses with the notion of good/evil points. Your actions don’t move a light side/dark side meter up or down, they simply have consequences. More importantly, those consequences are pretty brutal no matter which outcome you select. Not to digress too far, but my character in DA:O was a Casteless Dwarf, something akin to the burakumin of Japan, and her sister was a concubine for one of the noble families elevated in status because she produced a son (dwarves in this universe inherit caste from the same-sex parent). When I returned to the dwarf homeland, there was a bitter power struggle going on and it was up to me to choose to help who I thought should continue the disputed royal line. The obvious heir was a brutal man rumored to be the one who poisoned the his brother (and rightful heir to the throne) in the first place, but he was in favor of reform of the caste system and contact with the outside world. He was also my sister’s husband. The other candidate was in favor of a strong assembly (the legislative body) and, while he was a traditionalist, he was well-respected and, more importantly, not rumored to be a murderer. It then became a question of supporting a despotic butcher who would work to improve equality at the expense of representation (and also keep my family at a higher status) or a more traditional ruler who would rule without bloodshed, but keep my caste down and stay isolationist (not to mention assure that my sister’s place in society would be compromised). In the end I chose to side with my family, but I almost immediately regretted it when the man I chose ordered the execution of his rival immediately following his appointment. Not long after, the assembly was also dissolved. I made a hard choice that had no real good results for everyone and that’s ultimately what real life is about: grey areas.

Back to the question of whether or not to kill Morinth or Samara, here is another interesting moral decision. Samara made irresponsible choices and had not one Ardat-Yakshi (that’s what it’s called) offspring, but three. Morinth’s crimes, at this point, were many, but her only choices in life were to live as a prisoner or to run and live as a hunted criminal. Even then, if you’re like me you’re thinking that this really isn’t that much of a decision. It amounts to supporting a serial killer or supporting an irresponsible mother looking to bring her daughter to justice. No matter how bad I feel for Morinth’s predicament, I, personally, couldn’t support her because she’s a sociopath and a murderer. That’s the real rub with the Mass Effect universe. Despite how good it is, despite how great the narrative is, and despite how much I love the games, its decisions are a constant disappointment boiling down to, in most cases, “murder or mercy”. Dragon Age constantly forced me to choose between “murder and murder”. Kill one person who had good and bad qualities or kill another with the same qualities. I’m not saying that all real decisions in games have to revolve around murder, there were some legitimately tough choices to make in the first Mass Effect (that still ultimately boiled down to “m or m” on a grand scale), like whether or not to kill a terrorist or let him walk free (his hostages will die if you kill him) or whether or not to spare the Racchni or commit xenocide, but even they skirted around the much more important decision of whether or not to utilize the cure for the Krogan genophage. Your only option is to destroy it. (SIDEBAR: The Krogan people were forcibly infected with a genetic rewrite that causes 0.999 of all Krogran pregnancies to end in stillbirth (SIDEBAR: The Krogan reproduce very rapidly and are quite aggressive)).

This is a tremendous missed opportunity. Sure, the genophage is addressed in ME2 since it’s a central part of the Krogan species’ identity, but even then the decisions you make are irrelevant. If you destroy the work done to correct the genophage (again), the scientist in your team claims that it doesn’t matter anyway, since he could easily duplicate all of the results if he had to. Saving it or destroying it seems to have no real impact on the world of the game. Granted, I don’t need to control my destiny to such a fine level in the games I play, but when Bioware goes out of its way to explicitly claim that my decisions have a large, direct impact on the world, I begin to expect my decisions to make a difference. Even the major choices I made in the first game seem to only have cosmetic effects on the second. I might get a non-story-relevant message from a character stunned to learn that I was still alive or thanking me for saving them back then, but then there’s this one side quest that played out the exact same way no matter what I decided in Mass Effect, except that the character model talking to me and the spoken dialog were slightly different.

Yes, I realize that decisions having a real effect make the world exponentially more complicated, but you shouldn’t promise what you can’t deliver.

“[Mature] really has two meanings when we apply it to media. One is ‘not appropriate for children’ and the other is ‘exploring subject matter in a sophisticated fashion. Ironically, the word mature when applied to games tends to have a very childish connotation.”

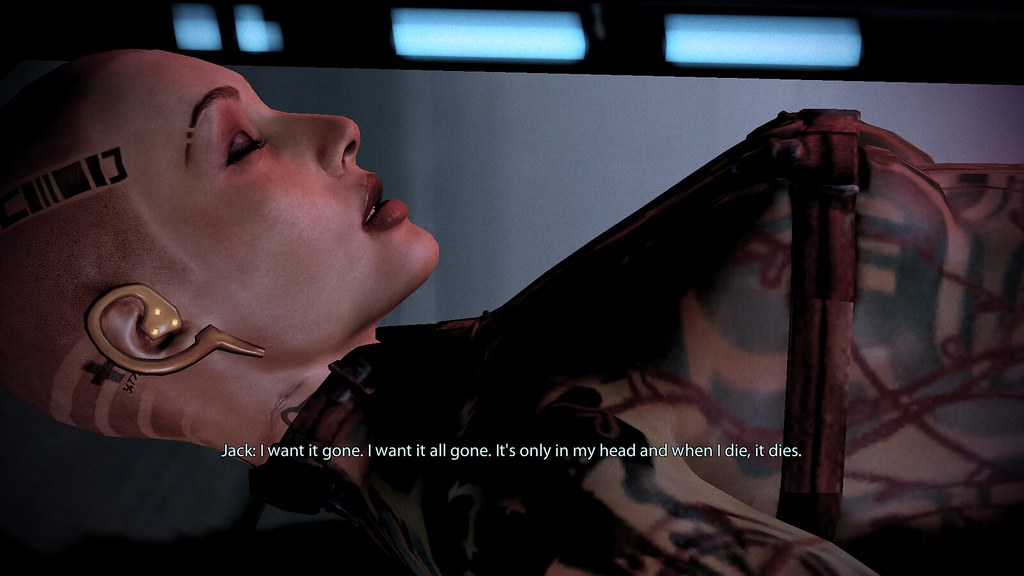

In late September of 2009 a Mass Effect 2 trailer highlighting Subject Zero was put out as part of the ME2 hype machine.

Needless to say, I became very concerned. It definitely did not fit in with the Bioware aesthetic and it felt like it was trying too hard to be edgy. This was the “maturity” that I’m always up in arms about and I was pretty worried that Bioware was going to take a serious misstep with their “dark second chapter”. After playing the whole game through, I’m confident in saying that Subject Zero and the characters in this “edgy” game were more or less about what you’d expect from Bioware in that they are decidedly not two-dimensional and are actually interesting. That’s not to say that Bioware didn’t make a few mistakes with its decision to go darker for this second game (they even redid their logo in blood red…it’s almost funny).

Subject Zero (AKA Jack) may have a “seriously abused child” story that fleshes her out and makes her character actually make sense, but that doesn’t mean that they made no mistakes with Jack. Her outfit, if you could even call it that, is absolutely ridiculous. It feels like a grab for the adolescent attention span by making her dress in what amounts to a pair of pants, some belts, and tattoos (if it wasn’t so blatantly sexual, it could be a Nomura design). When will game designers learn that dressing women in this way is not cool or interesting? All they’re doing is enforcing the stereotype and furthering the divide between gamer and non-gamer. Who could possibly see the way that Jack is dressed and think it was designed for anyone older than a 13-year-old male?

The other Bioware attempts at making the game more dark, serious, and mature seem to have been carried out much better than Subject Zero. Every planet or space station that is explored is appropriately seedy and grimy. Gone are the sterile, clean blues of the Mass Effect Citadel. In its place we have reds-orange slums, planets so dominated by commerce that slavery is legal, prison ships, and war-torn wastelands. Running into the formerly naïve and innocent Liara T’Soni from the first game is jarring and depressing when you see how she has become ruthless, cold, and calculated in her efforts to bring down the Shadow Broker. Even Shepard has changed in the eyes of the galactic community thanks to his involvement with the shady Cerberus terrorist organization.

Mass Effect 2 also benefits from the complex social situations set up by the lore itself. Credit is definitely well deserved for those responsible for the universe’s depth and background. Alien cultures are fleshed out and the interaction between them, humanity, and themselves feels genuine and interesting. In fact, aside from the fact that humanity seems like a brilliant race able to work wonders that others cannot (no doubt an extension of that same “white is might” mentality that is subconsciously behind Avatar, Pocahontas, Dances With Wolves, etc.), I find that we’re treated appropriately for an up-and-coming species that is rapidly stepping on so many toes. Actually, let’s take my parenthetical a little further: why is humanity a special species here? Why are we the only ones to accurately see the threat of Saren and The Collectors? in a galactic community featuring multiple sentient species, it hardly seems probable that the only one that is like the current Western world is humanity. Then again, why would aliens be anything like us, culturally? Why would future humanity continue to be so dominated by white men? These questions are kind of wandering around, so let me just say that having a token non-western cast that ensured inclusiveness might have seemed pander-y anyway. Next paragraph!

While we’re talking about tropes, I also find myself wondering about the impact that the trilogy structure on the story of ME2. The first game had a story that revolved around mind control, domination, and indoctrination that culminated in a plot twist about the real enemy and the insidious nature of the greatest scientific technologies that sentient life depended on. It had weight and purpose and things happened. ME2 seems to drag along, treading water the whole way. Your crew’s various backgrounds and backstories take center stage, but at the expense of anything that legitimately moves the plot forward save for two things: 1. You learn that The Collectors are genetically modified Protheans being manipulated by the Reapers and 2. You learn that a human-inspired Reaper is in the works (and you destroy it). All that says is that the Reapers have decided that humanity is its only legitimate threat and worthy of being adopted into their strange genetic-mechanical history, but that ultimately means nothing. Not one thing that happens in this chapter of the trilogy can compare to the Reaper bombshell of the first game. In terms of story, ME2 is just ME1.5 (or ME1.125).

Mechanics is where ME2 takes major strides away from ME1, but in a direction that is both welcome and distressing. Mass Effect was a serviceable third-person shooter with a super-clunky inventory and interface and unfun vehicle sections. It sounds harsh, but it really wasn’t all that bad for a freshman effort by an RPG company to make a shooter (notice the caveats!) and it was helped along by its strong narrative and much stronger conversation systems. ME2 brings what some might call a pretty good shooter to the table along with all the baggage that such a thing merits. Gone are many of the RPG elements of the first game (weapon skill, a glut of powers and passive skills, statistic-determined shot accuracy, and ammo types) and in are oversimplified options and a streamlined story structure to go with it. In a sense, Bioware did something right by avoiding pairing the slow, deliberate pace of the first game with the new, frenetic shooter engine, but at the cost of the weight of the narrative.

As I said before, the story is nothing to write home about and I attribute that mostly to the new mission structure that the game is hampered with. Each little action section takes place in an instanced area outside of the normal exploratory zones, lasts 20-30 minutes, finishes up whatever relevant story points are specific to that mission only, and then dumps the player out to a Mission Complete summary of their exploits as presented to the Illusive Man. I’m not sure what it is about the clear separation of action spaces and non-action spaces that peeves me so much, but I imagine it has everything to do with the way that the story parts were just as integrated with the action throughout most of Mass Effect. One sidequest in the original had me engaged in a firefight in the same exact place I’d just bought armor from half an hour ago. ME2 has rooms that the player can only access to start up their missions when said mission is available. There were very few locked doors in the first game. If I see one in ME2, I know a sidequest will take me there later. The zones in ME2 are merely hubs with shops and non-combat quests.

Combat quests are bizarrely chosen as the main mode of exposition in the game, which I’d normally be ok with, except that their focus is so laser-focused on whichever crew member’s backstory it is revealing that the third member of your party is often ignored. I couldn’t help but wonder why the game didn’t take advantage of my entire three-man squad in these story interaction moments since it’s always been my favorite part of Bioware games. For example, on Samara’s conversation-heavy loyalty quest, your third companion might as well not be there and he/she/it actually seems to disappear once it begins with no real explanation. He/she/it was there before we went into the apartment to investigate the murder, but then I didn’t see him/her/it again until after the mission. The lack of companion interaction is simply inexcusable after the shining examples set forth in the first game and Dragon Age: Origins. At any given quiet moment in DA:O, two of the companions following the Grey Warden can spontaneously burst into conversation about something. These talks are multi-topic connected affairs that have a complete arc to them throughout your travels. Mass Effect relegated these mostly to elevator rides around different places where they were there to help deal with the dead time in their concealed loading screens. Aside from one moment that I had to trigger in the Citadel by having two specific party members with me, there was not one bit of witty banter or conversation between my companions. I know this is supposed to be the “dark, serious second chapter”, but lighten up guys. We don’t have to spend our entire mission in steely, concentrated silence. A quip here or there would be more than welcome.

We can’t talk about things removed from the game without mentioning the Single Worst Thing About Mass Effect 1, the Mako tank. It handled poorly, was used for boring exploration, and was completely out of place with the rest of the game. It was like it was the 90s again and every game needed a vehicle section (game designer protip: we REALLY don’t need vehicle sections shoehorned into our games). Worst of all, it was associated with planetary exploration, a boring slog through the terrain of each planet to look for mineral resources and other artifacts that existed to provide money and experience. One correct lesson was learned and the Mako was excised from the game. The designers didn’t quite understand that a lot of the Mako hatred stemmed from planet resource mining, so they retained mineral mining in a different form. If you were the commander of an interplanetary space ship and you needed to mine resources from a planet, would you want to manually scan the planets yourself before sending down a probe to retrieve the resources? No, of course not. You’d have your engineering and mining teams handle all of that busy work while you managed other parts of the ship. As the player, I’m ostensibly Commander Shepard. There’s no reason why I have to tell the probes whrere to go. I don’t want to and it bores the hell out of me. If one aspect of your game (upgrades) is inexorably tied to a cripplingly boring aspect of your game (planetary scanning), then I think you need to reevaluate the way that you’re handling that first aspect

For my final nitpick of the game, I’d like to say that a PC version of a game should always have scroll wheel functionality if your interface allows for scrolling. Why do I have to click on a down button to scroll text? When are we living, the stone age?

By now I’ve realized that it looks like I really don’t like this game. I’ve got a lot of negative things to say about it precisely because I feel like it missed so many opportunities to be really great instead of just great. I wasn’t kidding when I said that the shooter mechanics were a leap forward. Everything from shooting enemies to throwing around biotic powers just feels crunchier. There’s no sweeter feeling than launching a ball of biotic push energy at a curve and watching it impact with a target and launch him off a platform. No. Sweeter. Feeling.

The game also offers just enough variety in its loyalty missions to keep them from becoming too stale. Most of them are combat affairs, but some, like Thane and Samara’s, feature no combat at all while others, like Jack or Tali, have combat interrupted by long conversations of narrative sequences which connect the player with the characters a bit more. Even Grunt’s straight arena setting is punctuated by a battle with a thresher maw whose mechanics are not seen again anywhere else in the game.

Despite the lack of real story, the game does also feature the best characterization I’ve seen in a while for a “dirty dozen”-style narrative structure. Team member depth varies widely (Zaeed has no dialog tree associated with him at all while Jack, Miranda, and Thane all feature long backstories and conversation trees), but each member does have a defined arc that is sometimes unique, funny, or tragic (or all three). Even non-party member crewmates have dialog allotted to them in more meaningful ways that the prior crew of the Normandy. This is all in the service of motivating the player to save them, which is another great narrative choice by Bioware.

SHORT DIGRESSION WHOSE PURPOSE WILL BE APPARENT SOON…

Whenever we want to talk about ludonarrative dissonance, Final Fantasy VII will inevitably come up. In the late game there is a meteor set to strike the earth after a fixed time period…except it isn’t. The player can spend millions of hours racing and breeding chocobos while staying in inns (which should technically be advancing time by a full day) instead of progressing the story. There is no point where the meteor strikes because Cloud was too busy hanging out at the Golden Saucer playing a stupid snowboarding game. The narrative is at the player’s mercy.

Every person who plays Mass Effect 2 will have his crew (minus combat party members) abducted by The Collectors in the endgame. Most players probably think they can continue to fool around and expect to save the crew before they are killed. I completed all the sidequests expecting that I wouldn’t be able to return to them and in the interest of boosting my level higher. When I finally reached my crew in the endgame, all but one (or two…it’s not many) had been murdered. Granted, that one will always survive no matter how long you take breeding chocobos (aka: scanning minerals), but the rest of your crew is permadead, leaving your ship empty in the open-ended postgame.

There’s not enough of this in video games. If you’re telling me to hurry and do something, I’d better damn well have to hurry, because otherwise I feel cheated when I see the man behind the curtain. JRPGs may be the biggest offender in this dissonance, but it’s not alone. Consider the heavily scripted shooter where I can spot the “actors” up ahead standing stationary until I get close enough to trigger the event that kills them. I can stand for an eternity watching my comrades stand in an exposed corridor with shooters at the end, but they’ll never die until I get close. Counter that with Dead Rising and its brutal time system. If you wait until 1600 on Day 2 to save this one person, guess what? He won’t be there. The zombies killed him. If you don’t complete the next story objective before the timer runs out, the rest of the game is closed off to you. Events will no longer transpire in that way and you’d better reload your save. That makes perfect sense for a game where haste and time management are issues. When someone tells you to do something quickly, they mean it. I don’t like to be blatantly lied to. Mass Effect 2 is honest in that respect.

I guess that’s really all I have to say about Mass Effect 2. It’s a fine game that you should own, but it also brings up a lot of issues about game design that I hope Bioware confronts for the concluding chapter of the saga.

Leave a Reply